Shallow Water Blackout

If you’re like most Scuba Divers, what you likely remember about shallow water blackout – the sudden loss of consciousness due to oxygen starvation – is that it happens in shallow water while free diving. But given the growing interest in snorkelling and free diving, especially as a family activity, your working knowledge of this life-threatening malady needs to be more than just a vague memory.

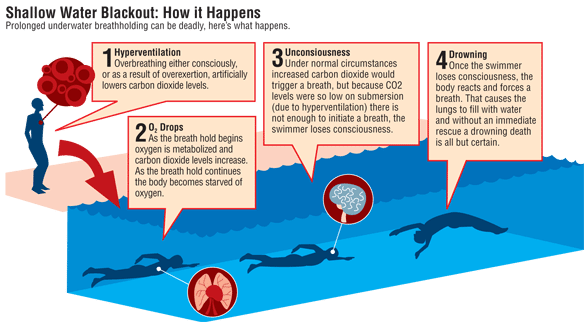

The form of shallow water blackout that most of us are familiar with occurs primarily among breath-hold divers. A common technique when free diving is to hyperventilate before a dive – increasing the rate and depth of respirations. This “blows off” carbon dioxide in the system so that you start the dive with less carbon dioxide in your blood than you would otherwise. This technique allows you to stay down longer because it is elevated carbon dioxide levels in the blood that signal the brain that the body needs to breathe. By starting a breath-hold dive with less carbon dioxide in your blood, it takes you longer to build up carbon dioxide to the point where you feel the urge to breathe.

How Hyperventilation Causes Shallow Water Blackout:

The downside is that hyperventilation can bring on the condition of hypoxia, or lack of oxygen. The partial pressure of oxygen at sea level is .21 atmospheres (ATA). The brain requires a minimum partial pressure of oxygen of .10 ATA in order for you to remain conscious. Hyperventilation can drop you below that level.

Here’s what usually happens:

When a diver hyperventilates to reduce his body’s carbon dioxide level, he also slightly increases his oxygen partial pressure level to around .24 ATA. He then dives to a depth of 33 feet, doubling the pressure he is under, which also doubles the partial pressure of oxygen in his lungs to .48, according to Boyle’s Law. During the dive he extracts oxygen from his lungs, and slowly replaces it with carbon dioxide. By the time carbon dioxide accumulates sufficiently that the diver needs to surface, the oxygen partial pressure in his lungs is .15 ATA, but the diver is still at 33 feet. As he ascends, both he and the gas in his lungs are under less and less pressure, until he reaches the surface where, assuming an oxygen partial pressure of .15 ATA at depth, he would now have an oxygen partial pressure of .075 – less than that needed to maintain consciousness. Therefore, at some point before reaching the surface (usually between 10 and 15 feet), this diver would black out, instantaneously and without warning.

Diving and Snorkelling:

Is It Safe? What are the risks then, if any, of diving after snorkelling, or vice versa? Recreational snorkelling and free diving, because of the relatively short time spent at depth, do not result in any significant nitrogen build up in the blood or tissues. Therefore, there is little to no risk in diving after snorkelling.

However, the reverse is not necessarily true. It is well-known that tiny bubbles appear in many divers’ bloodstreams after diving. These bubbles are usually filtered from the blood as it passes through the lungs without causing any problems.

But if a diver with these micro-bubbles were to dive to a depth where the pressure forced these bubbles back into solution, and then ascend rapidly – as breath-hold divers do – these bubbles would come back out of solution, potentially as much larger bubbles that could result in symptoms of DCS. The depths at which the tiny bubbles would be forced back into solution are variable, but could occur at depths as shallow as 30 feet, well within the range of most snorkelers.

This potential risk can be easily eliminated by avoiding any deep free dives (below 15 feet) after scuba diving. So enjoy your snorkelling surface intervals, but remember to stay close to the surface and to wear a skin or T-shirt to protect your back from the sun.